Butts, Jeffrey A. and Sheyla A. Delgado (2017). Repairing Trust: Young Men in Neighborhoods with Cure Violence Programs Report Growing Confidence in Police [JohnJayREC Research Brief 2017-01]. New York, NY: John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Research and Evaluation Center.

Butts, Jeffrey A. and Sheyla A. Delgado (2017). Repairing Trust: Young Men in Neighborhoods with Cure Violence Programs Report Growing Confidence in Police [JohnJayREC Research Brief 2017-01]. New York, NY: John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Research and Evaluation Center.

Introduction

As part of an ongoing evaluation of the Cure Violence strategy, researchers found the program was potentially associated with less support for the use of violence and greater confidence in police. In a series of neighborhood surveys, young men in areas with Cure Violence programs were less likely to use violence to settle personal disputes and more likely to rely on law enforcement.

Cure Violence (CV) is a place-based, public-health approach to violence reduction that relies on “outreach workers” and “violence interrupters” to prevent high-risk individuals from using violence to resolve conflicts. Cure Violence workers try to “denormalize” violence by reducing the social norms that perpetuate it while simultaneously intervening to change the behavior of the community residents most likely to resort to violence (Butts et al. 2015).

John Jay College (JohnJayREC) is evaluating the effectiveness of Cure Violence in New York City with funding support from New York City government and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation of Princeton, NJ. As part of that study, researchers surveyed thousands of young men ages 18 to 30 in disadvantaged neighborhoods of New York City. Some areas were operating Cure Violence programs and some were not.

All surveys were administered with tablet computers and complete confidentiality. The study did not obtain or record any respondent’s personal information. All answers were collected by touch screen, allowing respondents to engage with the questionnaire privately if they chose. The study generated a sample of 180-200 respondents in each neighborhood using “respondent-driven sampling,” a recruitment strategy that relies on the social networks of respondents (Blount-Hill and Butts 2015).

Analysis

This research brief examines survey data collected from 2014 to 2016 in two neighborhoods with well-established Cure Violence programs: Man Up! Inc. in East New York, Brooklyn, and S.O.S. South Bronx, a program operated by the Center for Court Innovation.(1) Researchers matched each of these areas with similar neighborhoods that did not have Cure Violence programs: East Harlem and a section of Brooklyn known as Flatbush. Surveys were conducted using identical methods in all four areas.

(1). Man Up! Inc. operates two Cure Violence programs in Brooklyn. This study examines the agency’s “Alpha” site, or Man Up! Inc. (A).

The survey estimated confidence in police using two questions with Likert-scale responses from “No Definitely” to “Yes Definitely.” The two questions were: “When violence breaks out, can you and your neighbors count on the police to help?” and “If you saw someone being beaten up or shot, would you call the police to report the crime?” Both measures improved in all neighborhoods, but areas with Cure Violence programs experienced larger gains that were statistically significant (see graphic).

The evaluation’s main goal was to test the association between Cure Violence and social norms, but the survey data also allowed researchers to examine relationships between norms and confidence in police. To measure violence-supporting norms, respondents reacted to 17 hypothetical scenarios involving varying levels of conflict, including competition over intimate partners, retaliation for previous violence, disputes over debts and stolen property, and challenges to social identity, status, and territory (e.g., outsiders trying to use our basketball court) (Delgado et al. 2015). Respondents reacted to each scenario by choosing from a scale of 10 possible behaviors, ranging from “I would ignore it,” to “I would react verbally,” to I would “pull a weapon” or “use a weapon.”

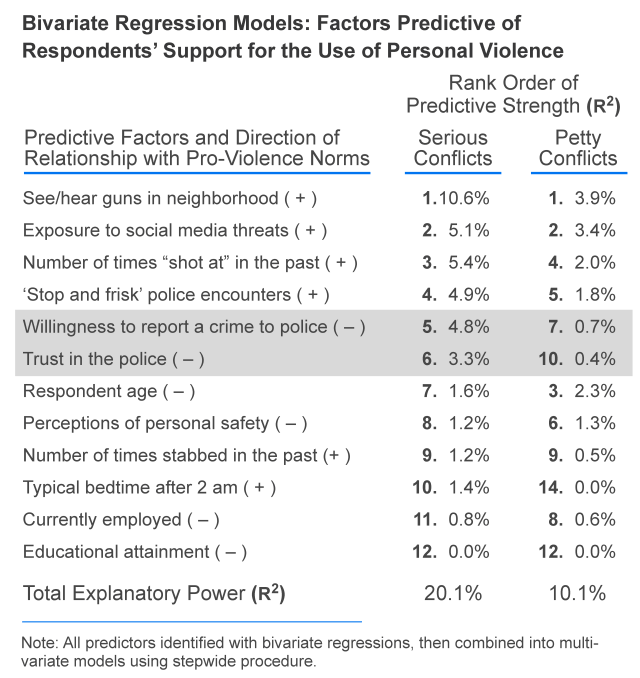

After splitting the scenarios into two distinct indices reflecting “petty” conflicts (e.g., someone stepped on my new shoes) and “serious” conflicts (e.g., someone refused to pay a debt), researchers used regression analysis to examine the factors that predicted respondents’ reactions (see Table). In both types of conflict, the top two predictors of support for violence were the respondent’s prior exposure to gun violence (e.g., seeing guns in the neighborhood, hearing shots, etc.) and witnessing violent threats in social media platforms. In other words, respondents who saw gun violence in their social environment were more likely to support the use of violence themselves.

Two other strong predictors were respondents’ experiences with being the target of gun violence (i.e. ever been “shot at”) and the number of times they had been “stopped and frisked” by police in the past year. Respondent age was the third strongest predictor for petty conflicts (lowering support for violence), but only the seventh strongest predictor for serious conflicts. In scenarios involving serious conflicts, the fifth and sixth strongest predictors were the respondents’ willingness to report crime and their trust in law enforcement. Respondents expressing more confidence in police were significantly less likely to support the use of violence in serious disputes.

Finally, researchers used regression analyses to test the effects of time on each measure of confidence in law enforcement. Four models were fitted with all useful predictors associated with respondents’ confidence in police. In each model, a variable representing the passage of time was included to estimate the change in confidence from 2014 to 2016.

The coefficient for time was significant in both models for neighborhoods with Cure Violence programs, but not significant in neighborhoods without Cure Violence programs. In other words, after controlling for all other influences, confidence in law enforcement was increasing the most in Cure Violence neighborhoods.

Conclusion

The results of this research brief suggest that confidence in police grew across New York City between 2014 and 2016, but it appeared to grow more in neighborhoods served by Cure Violence programs. Young men living in Cure Violence areas also reported decreasing support for the use of violence to settle personal disputes. These findings are suggestive. The analysis does not establish the direction of causality between violence norms and confidence in law enforcement, but it underscores an association between the two and points to police legitimacy as another possible benefit of successful efforts to reduce community violence.

References

Butts, Jeffrey A., Caterina Gouvis Roman, Lindsay Bostwick, and Jeremy Porter (2015). Cure Violence: A Public Health Model to Reduce Gun Violence. Annual Review of Public Health, 2015 (36): 39–53.

Delgado, Sheyla A., Kwan-Lamar Blount-Hill, Marissa Mandala, and Jeffrey A. Butts (2015). Perceptions of Violence: Surveying Young Males in New York City. New York, NY: Research & Evaluation Center, John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Blount-Hill, Kwan-Lamar and Jeffrey A. Butts (2015). Respondent-Driven Sampling: Evaluating the Effects of the Cure Violence Model with Neighborhood Surveys. New York, NY: Research & Evaluation Center, John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding support provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the New York City Council, and the NYC Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. The authors are grateful for the cooperation and support of the hundreds of New York City residents who participated in the surveys on which this research brief is based. Points of view or opinions contained within this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of John Jay College, the City University of New York, or any of the organizations funding JohnJayREC projects.

RECOMMENDED CITATION

Butts, Jeffrey A. and Sheyla A. Delgado (2017). Repairing Trust: Young Men in Neighborhoods with Cure Violence Programs Report Growing Confidence in Police [JohnJayREC Research Brief 2017-01]. New York, NY: John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Research and Evaluation Center.