Jeffrey Butts and Jeremy Travis (2002). The Rise and Fall of American Youth Violence: 1980 to 2000. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Researchers will debate for years why violent crime in the United States increased sharply in the 1980s and early 1990s before dropping just as precipitously in the mid- to late-1990s. All researchers agree, however, that general trends in violent crime during this period had much to do with changing rates of youth crime. This report examines these trends and analyzes what portion of the recent crime drop can be attributed to juveniles (under age 18) and young adults (ages 18 to 24). The results demonstrate that while young people helped to generate the growth in violence before 1994, they contributed an even more disproportionate share to the decline in violence after 1994. Most of the recent decline in violent crime, in fact, was due to falling rates of violent crime among the young.

Introduction

Researchers will debate for years why violent crime in the United States increased sharply in the 1980s and early 1990s before dropping just as precipitously in the mid- to late-1990s. All researchers agree, however, that general trends in violent crime during this period had much to do with changing rates of youth crime.

With the recent release of crime data for the year 2000, it is possible to review crime trends over the entire span of years between 1980 and 2000. This report examines these trends and analyzes what portion of the recent crime drop can be attributed to juveniles (under age 18) and young adults (ages 18 to 24). [1]

The results demonstrate that while young people helped to generate the growth in violence before 1994, they contributed an even more disproportionate share to the decline in violence after 1994. Most of the recent decline in violent crime, in fact, was due to falling rates of violent crime among the young.

1. This analysis builds upon information contained in Youth Crime Drop, published by the Urban Institute in December 2000. The earlier report included data about arrests through the year 1999. This report presents arrest data through 2000, the most recent year for which information is available from the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program.

The Ups and Downs of Violent Crime

A decade ago, Americans faced frightening predictions about an approaching storm of juvenile violence. Popular terms from the early 1990s, such as “juvenile super predator,” “coming blood bath,” and “crime time bomb,” suggested the nation was heading toward an unavoidable collision with a growing generation of violent youth.

Indeed, the United States experienced sharply growing rates of juvenile violence duringthe 1980s and early 1990s. If these trends had continued, it would have caused a national crisis. The number of juvenile arrests for Violent Index offenses (i.e., murder, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault) grew 64 percent between 1980 and 1994. Juvenile arrests for murder jumped 99 percent during that time. The juvenile arrest rate for murder shot up 167 percent between 1984 and 1993 alone, from a rate of 5 arrests per 100,000 juveniles to 14 per 100,000.

By the early 1990s, violent juvenile crime had captured the attention of the nation’s policymakers and news media, as well as the public. Nearly every State in the country had launched new juvenile justice reform initiatives, often involving reduced judicial discretion and a greater use of adult court for juvenile offenders. The juvenile justice system was widely criticized as soft and ineffectual. Pundits and some crime researchers were predicting the next decade would be even worse.

If the rate of juvenile violent crime were simply a function of the size of the juvenile population, researchers in the early 1990s had good reason to be concerned. The number of juveniles in the U.S. population was expected to grow significantly. The number of Americans between the ages of 10 and 17 had declined throughout the 1980s, reaching a low of 27 million in 1990, but the U.S. Census Bureau projected in 1993 that this population could grow more than 20 percent over the next two decades, perhaps reaching 33 million by the year 2010. [2] Such projections, in combination with the growth in violent crime through 1994, led some researchers to warn the nation about a coming wave of juvenile violence that would hit during the 1990s and last for more than a decade.

2. Bureau of the Census (1993).Current Population Reports, Population Projections of the United States, by Age, Sex, Race and Hispanic Origin: 1993 to 2050. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census.

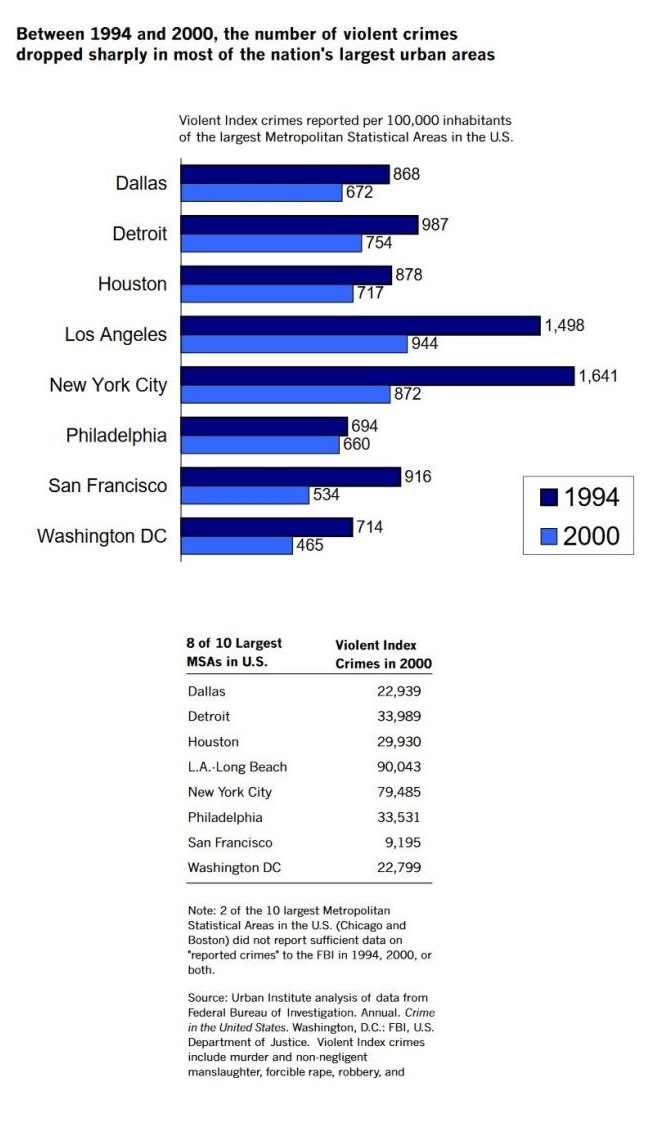

Predicting violent crime trends, however, is not that simple. The 1993 Census Bureau estimates turned out to be correct. By the end of the century, the population of 10 to 17 year-olds in the U.S. population exceeded 31 million. [3] Yet, violent crime in America fell for six straight years from 1994 to 2000. According to the newest crime data released by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the rate of juvenile violent crime in 2000 was lower than at any time in the previous two decades.

3. Bureau of the Census (2001). National residential population estimates by age. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Population Projections Branch.

We may never learn the exact reasons for this sudden turnaround, but researchers have proposed a number of hypotheses. Explanations for the crime decline include the influence of a strong economy during the late 1990s, growing cultural intolerance for violent behavior, changes in the market for illegal drugs, new policies to regulate access to firearms, expanded imprisonment, the growth of community policing, and other criminal justice innovations. Detailed analyses suggest that each of these factors may have been involved, but it is impossible to isolate the independent effects of such broad social forces and widespread policy innovations (Blumstein and Wallman, 2000; Travis and Waul, forthcoming).

Regardless of how one wishes to explain the decline in violent crime, one thing is clear. The falling rate of violence in American communities during the late 1990s was disproportionately caused by young people, confounding predictions that the increase in juvenile violence between 1980 and 1994 presaged a coming generation of “super predators.”

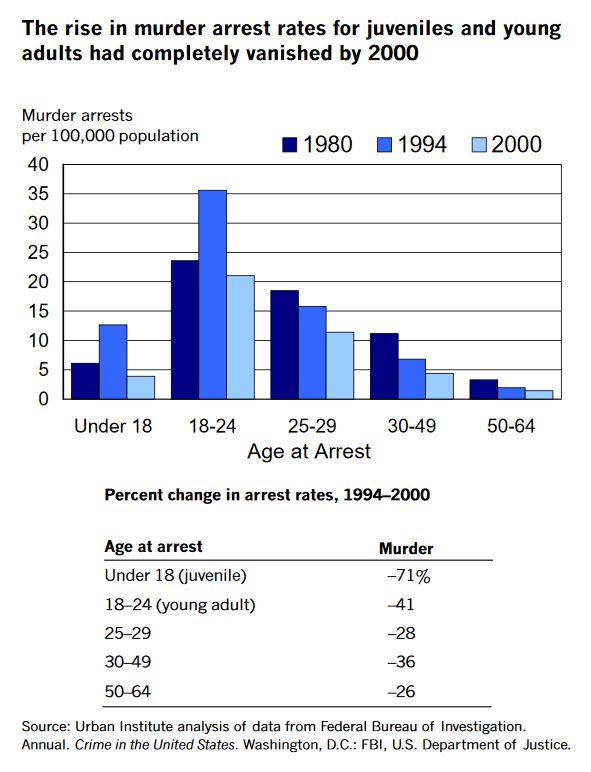

The Drop in Juvenile Crime

In 2000, U.S. law enforcement agencies made an estimated 14 million arrests. Of these, 17 percent (or 2.4 million arrests) involved juveniles under age 18. The number of arrests involving juveniles in 2000 was 13 percent lower than the number in 1994. Arrests for many of the most serious offenses fell even more sharply. Between 1994 and 2000, arrests for murder dropped 68 percent among juveniles, robbery arrests were 51 percent lower, burglary arrests fell 33 percent, and juvenile arrests for motor vehicle theft were down 42 percent.

The total decline in juvenile arrests (–13 percent) would have been larger if not for offsetting increases in arrests for some of the less serious offenses. For example, juvenile arrests for driving under the influence were up 54 percent between 1994 and 2000, liquor law violations grew 33 percent, and arrests for drug abuse violations increased 29 percent.

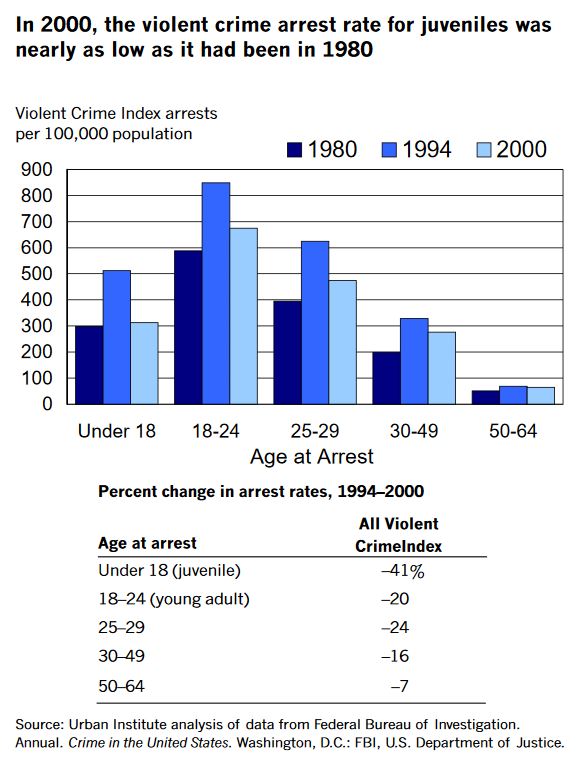

Studies of changes in violent crime should always consider the possibility that fluctuations in the juvenile population may be responsible for the trends in juvenile arrests reported by law enforcement agencies. This was not the case during the recent drop in violent crime. Even controlling for changes in the population, the rate of decline in juvenile arrests between 1994 and 2000 was striking, and it outpaced that of other age groups.

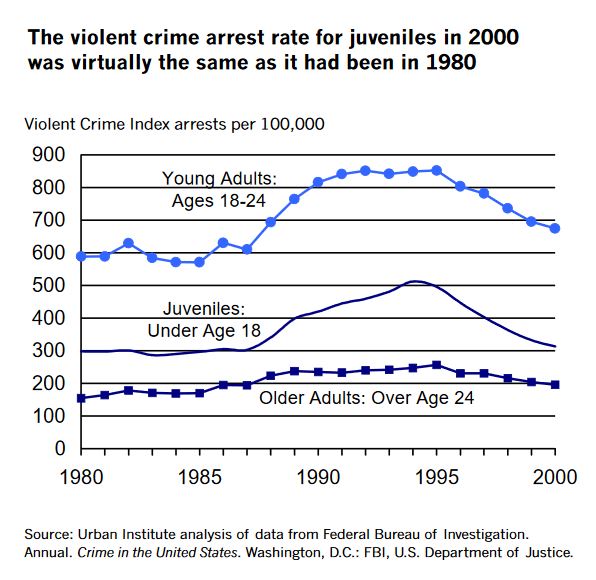

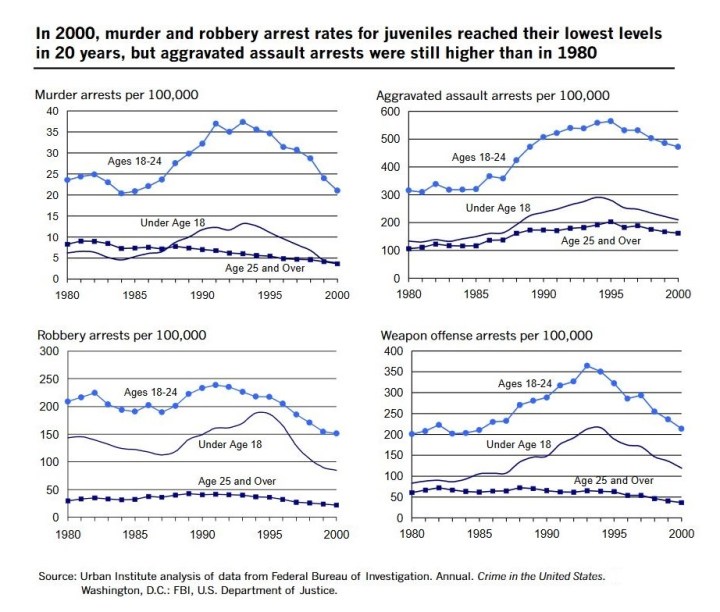

For every 100,000 juveniles age 10 to 17 in the U.S. population during 2000, there were more than 300 juvenile arrests for the four Violent Crime Index offenses combined (i.e., murder, forcible rape, aggravated assault, and robbery). The violent crime arrest rate fell among every age group between 1994 and 2000, but the decline was proportionally larger among juveniles. The juvenile arrest rate for Violent Crime Index offenses in 2000 was less than two-thirds the rate of 1994.

The arrest rate for murder also fell for every age group between 1994 and 2000. Among older adults (over age 24), the drop continued a downward trend that had existed for two decades. The sudden drop in murder arrests for juveniles and young adults completely reversed the increases seen prior to 1994 and brought down murder arrest rates to levels below those of 1980.

Arrest rates for young adults (ages 18 to 24) remained consistently higher than rates for juveniles throughout the period between 1980 and 2000. In 2000, the violent crime arrest rate for offenders between the ages of 18 and 24 was more than double the rate for juveniles under age 18. The arrest rate for murder among 18 to 24 year-olds was four times that of the murder arrest rate among juveniles.

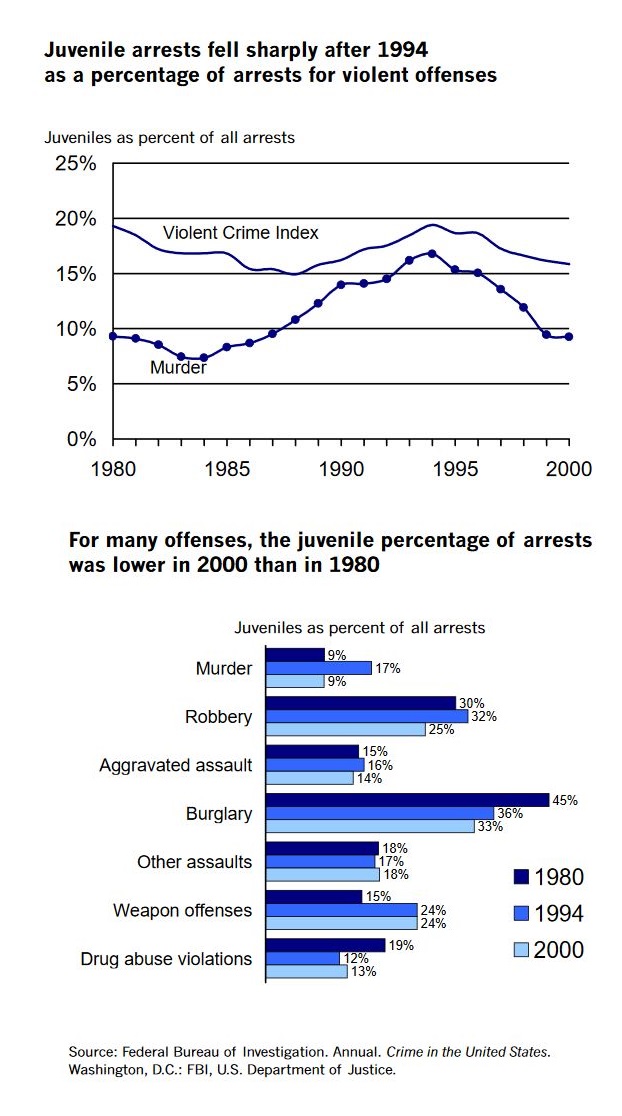

If juvenile arrests decline more than arrests involving older offenders, the relative proportion of juveniles among all those arrested will necessarily fall. This effect is clear when one examines FBI data on juvenile arrests as a proportion of all arrests for various offenses.

In 2000, juveniles accounted for 16 percent of all arrests for Violent Crime Index offenses, down considerably from 1994 when juveniles accounted for 19 percent of violent crime arrests. Juveniles were involved in 9 percent of murder arrests in 2000, compared with the peak of 1994 when they made up 17 percent of murder arrests. For several offenses, including robbery, burglary, and drug abuse violations, juveniles accounted for a substantially smaller proportion of arrests in 2000 than they had in 1980.

The Youth Contribution to Declining Violent Crime

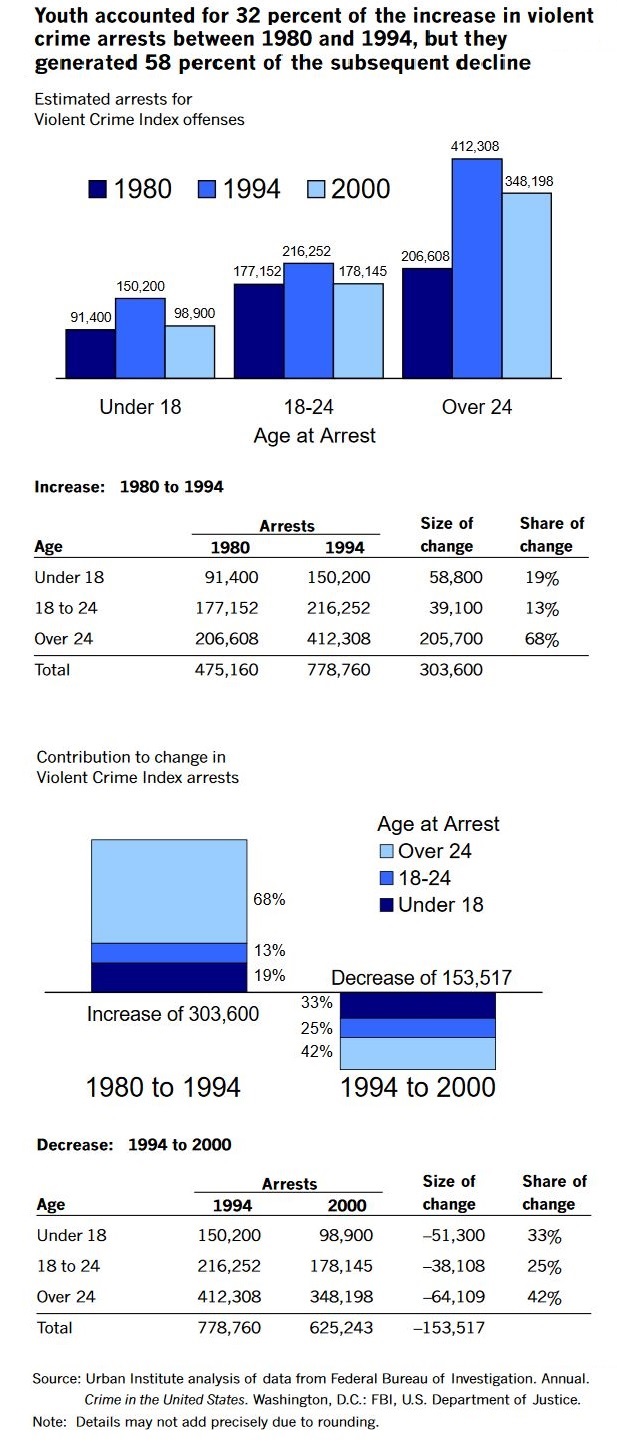

Having demonstrated that the decline in youth violence, as measured by arrests of young people age 24 and younger, was steeper than the decline in violent crime among older age groups, this analysis turns to a related question: How much of the overall violent crime drop in America was due to changes in youth crime? The question is answered by examining the age composition of the relative increases and decreases in arrests between 1980 and 2000.

According to the FBI publication series, Crime in the United States, there were nearly 779,000 total arrests for Violent Crime Index offenses in 1994, and more than 625,000 in 2000 (national estimates). Thus, there were approximately 150,000 (or 20 percent) fewer violent crime arrests in 2000 than in 1994 (all ages combined).

The contribution of each age group to the drop in violent crime arrests can be estimated by calculating the decrease in the number of arrests involving that group and comparing it to the decrease for offenders of all ages. The results of this comparison suggest that juveniles accounted for a decline of 51,300 arrests — i.e., 33 percent of the overall decrease in violent crime arrests between 1994 and 2000. Young adults, on the other hand, accounted for 25 percent of the decline, while adults ages 25 and older accounted for 42 percent of the total decrease. In contrast, juvenile offenders accounted for just 19 percent of the increase in violent crime arrests between 1980 and 1994, while young adults accounted for only 13 percent.

Thus, juveniles and young adults combined (all youth under age 24) were responsible for 32 percent of the increase in violent crime arrests between 1980 and 1994, but they accounted for 58 percent of the subsequent drop in arrests between 1994 and 2000.

New Strategies for Crime Control

Whatever forces combined to produce the drop in violent crime after 1994, they appear to have had their strongest effects on young people, the very demographic group that some experts believed would overwhelm American society by the end of the 1990s with alarmingly high levels of violence. The juvenile “super predators” did not appear as predicted. In fact, young people were arrested for violent crime at about the same rate in 2000 as they had been in the early 1980s, and at even lower rates for some violent crimes such as robbery.

Clearly, something happened to cause the increase in violent youth crime seen during the 1980s and early 1990s, and just as clearly, other factors combined to bring down violent crime after 1994. Such rapid changes in violent behavior argue against the hypothesis of demographic inevitability that led some researchers to predict a violent crime wave in the late 1990s. Rather, crime trends over the past two decades suggest that changes in violent crime may be associated with fluctuations in unemployment and economic distress, the nexus between violent drug markets and firearms, and general levels of community disorder and the quality of everyday life for children, youth, and families.

Perhaps the key question for future policy and research is whether a particular combination of social forces sets off each wave of juvenile violence. In a volatile social environment, researchers should routinely monitor community conditions as well as the attitudes and expressed norms of young people to understand better what behaviors are considered inappropriate and unacceptable within the youth population. A research program to detect “tipping points” in these conditions and attitudes may help communities anticipate and avoid the next sudden increase in youth violence.

_________________________________

References

Blumstein, Alfred, and Joel Wallman, editors. 2000. The Crime Drop in America. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. Annual. Crime in the United States. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice.

Snyder, Howard. 2000. Juvenile Arrests 1999. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention [NCJ185236].

Travis, Jeremy, and Michele Waul. Forthcoming. Reflections on the Crime Decline: Lessons for the Future. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute.

_________________________________

© 2002 The Urban Institute

2100 M Street, NW

Washington, DC 20037

http://www.urban.org

(202) 833-7200

The Urban Institute is a nonprofit policy research organization established in Washington, D.C., in 1968. The Institute’s goals are to sharpen thinking about society’s problems and efforts to solve them, improve government decisions and their implementation, and increase citizens’ awareness about important public choices.

The Justice Policy Center carries out nonpartisan research to inform the national dialogue on crime, justice, and community safety. JPC researchers collaborate with practitioners, public officials, and community groups to make the Center’s research useful not only to decisionmakers and agencies in the justice system but also to the neighborhoods and communities harmed by crime and disorder.

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders.

Youth depicted in the photographs are models and are used for illustrative purposes only.

Designed by David Williams